A Coda For My Musical Mentor

My uncle James O’Malley passed away late last month. Were it not for him, I might not have discovered music beyond "Jock Jams"—or become who I am today.

On a Wednesday afternoon in late March, my uncle James O’Malley sat smoking a cigarette in his backyard on the outskirts of Austin. His cowboy hat was tilted low over his sunglasses, and he cracked jokes as a light breeze stirred the wind chimes. If you didn’t notice how skinny he’d gotten under his faded purple shirt, and if you hadn’t seen how much effort it took him to get into his wheelchair that morning, you could almost pretend he wasn’t dying.

About a week earlier, James had decided to shift to at-home hospice care after a long and painful battle with Type 1 Diabetes and a host of related health issues. This meant stopping his thrice-weekly dialysis. And with his kidneys failing, it would only be a matter of time before he was gone.

I had hopped on a plane from New York to Texas as soon as I could. The first two days I was there, James seemed to be getting weaker and weaker. But on the third, he perked up, and asked if we could go all outside. And so we joined him on the patio: his wife, Mary Beth; his son, Neil; his daughter, Bridget; a couple of cousins; several close friends; and me.

We reminisced about James’s favorite things, from marijuana strains to the live shows of Neil Young (after whom my uncle named his own son). James always had a dark sense of humor, and it was on full display that Wednesday. When he coughed after Mary Beth deposited liquid pain medication into his mouth, he quipped: “She’s trying to kill me!”

That turned out to be his last afternoon on Earth.

But James wouldn’t want to be remembered solely as he was that day, even though he retained the core of his character until the very end. He’d want to be thought of as a man of many passions—as a loving father and husband, a fiercely loyal friend, a Michelin-level chef, a gifted visual artist, and a world-class wit. There have been several tributes elsewhere focusing on exactly that.

Today, though, I’d like to share a few recollections of the person who supercharged my interest in music more than anyone else on the planet. If it weren’t for James—a talented singer-songwriter in his own right—my tastes might have never evolved beyond the Jock Jams compilations of the mid-1990s. And I wouldn’t be the human I am today.

When I was growing up, the dining room of my New York City home was dominated by an oil-on-canvas piece that took up almost an entire wall. In the center of the painting stood a wildly colorful creature who resembled nothing I’d ever seen before, or since. It looked like the number pi—if it had turned into a dinosaur and then dropped acid—lurching eagerly toward the heavens.

James had painted it, presumably when he was in art school, and given it to my parents at some point. Before I was born, they would invite him up to New York for long visits, and when he was in high school, they encouraged him to apply to elite northeastern art schools like RISD and Pratt. He got into both, but decided to stay closer to home in Texas.

He married my aunt Mary Beth in 1987, just before my second birthday, and I wore a little gold tuxedo to the ceremony on a rare snowy night in El Paso. Apparently, I ate so much cake at the reception that I started walking backward until someone scooped me up and took me to bed. The newlyweds eventually settled in Austin.

For me, James started out as Uncle Jimmy, my mom’s impossibly cool younger brother. In one of my favorite pictures, I’m on his shoulders as a toddler, looking a little uncomfortable on a windswept beach. James smiles and flashes a peace sign, knees in the sand, his jeans splattered with paint.

I think it was his mission to make sure I didn’t end up being another square city kid. When I was seven or eight, he tried to show me how to skin a catfish at my grandpa’s North Texas farm (he did not succeed). A few years later, he attempted to teach me perspective in visual art (a bit more luck there). And throughout, he’d remind me not to take things too seriously—life was too short not to have a sense of humor about it (I like to think he nailed that one).

As a kid, I used to spend a month every summer with my grandparents in Dallas. But after my grandpa passed away in 1996, my grandma started spending more time in Austin, especially since James and Mary Beth had just welcomed Neil and Bridget into the world. And so, the self-proclaimed “Live Music Capital of the World” became the focal point of my annual summer trips to Texas.

I’ve got so many great memories of those trips, but I will remember James above all as he was in the summer of 1998, when I was 13. From head to toe, he embodied Gen X cool: firecracker red curls, pale blue eyes, a Son Volt t-shirt, faded jeans, and purple Chuck Taylors. He said things like “dude” and “man” and “right on” and “far out” without a hint of irony or poserism.

At that point, my musical tastes went about as far as my latest middle school dance party playlist. The prior school year, my seventh-grade compatriots and I had rocked mostly been rocking out to songs that weren’t exactly Coachella material.

“The Macarena.” “As Long As You Love Me.” “Cotton Eye Joe.”

So when James and I started talking about music that summer, I think he saw a chance to teach me something even more useful than catfish deconstruction. James never lectured. But when we drove to Round Rock for a minor league baseball game or to Lake Travis for some frisbee golf, he’d crank 101-X or KGSR in my grandma’s baby-blue Cadillac. And I fell in love with the noise made by an electric guitar.

Nirvana. Pearl Jam. Stone Temple Pilots.

It was like someone had added a new dimension to sound.

Red Hot Chili Peppers. The Offspring. Blink-182.

James let the music do most of the talking. He started giving me some of his favorite CDs (his own copies!) And I’d listen to them on my Sony Discman every night as I fell asleep on the futon in the living room. If a CD skipped, I’d try the tricks James taught me: licking the back of the disc or rubbing it on my oily adolescent forehead (it worked!) And then I got right back to being transported.

Californication. Nevermind. No Code.

At the time, James was running a custom framing shop called Zuma—named, of course, after the Neil Young album—and he got tons of business from local stations and radio personalities. He also received a flood of free albums and passed them along to me. Some of the bands were extremely random.

Squirrel Nut Zippers. Dynamite Hack. Ugly Americans.

James also got scads of free concert tickets. My first music festival was the Warped Tour at South Park Meadows, with a lineup that included Bad Religion, NOFX, and the Cherry Poppin’ Daddies (wow). I still remember how a guy in a leather jacket and full mohawk jumped up and down in the midday Texas heat for the entirety of Rancid’s set.

After spending a summer evening downtown watching a local band called George DeVore & the Roam, James got us invited to the afterparty. It was at a nondescript suburban house, but the backyard had a pool, and there were several scantily clad ladies in it. We stayed well past midnight; I even got to meet George, who graciously chatted with me before disappearing into a back room, probably with one of the ladies.

I went back to New York with a suitcase full of CDs, my uncle’s Red Hot Chili Peppers baseball shirt, and my own newfound obsession with music. My aunt came up that fall with her sister and took me to my first arena show: Pearl Jam at Madison Square Garden.

That winter, I listened to Nirvana’s Nevermind so many times that a thin crack formed on the inner ring of the disc. Then it crept up into the part where the music was stored. Then it widened and physically broke in half.

So I signed up for a Columbia House mail order subscription: 12 CDs for $1 up front (and a full $15 for one CD per month after that, which my allowance barely covered). On top of a fresh copy of Nevermind, I added new albums.

Third Eye Blind. Everclear. Foo Fighters.

Expanding my tastes expanded my mind, and somehow later helped me find my way to the genre that changed my life most of all: hip-hop. I just couldn’t get enough of music.

All through eighth grade, I’d come home from school, turn on 1080 Snowboarding for Nintendo 64, and crank up my old Aiwa boombox. Whether attempting to drown out the parting shots of my parents’ eight-year-long divorce or just the typical growing pains of adolescence, music helped me escape.

More specifically, certain records—the music that James turned me on to—helped me escape.

I kept up my trips to Austin as I got older, and James always had some exciting new album—or experience—for me. He kept telling me about this up-and-coming music festival called South By Southwest, but the timing never quite lined up with my school breaks. Still, I knew I could always count on his calls on my birthday, or on holidays when I wasn’t able to visit, starting with his familiar jovial exclamation: “Hey, Zackaroo!” And maybe a surprise CD in the mail, like the time he got me a signed copy of Everclear’s highly anticipated follow-up to So Much For The Afterglow.

At some point in high school, I told James I’d never smoked weed, and wanted to know what it felt like. He offered to show me the ropes, figuring his supply would be safer than whatever I might stumble into back home. So, one night, we sat in the Cadillac before a show at Antone’s, and I lit up his little wooden pipe. We waited awhile, and I didn’t feel anything. But when I tried to take another hit, I burnt my eyebrow. Then I imagined my head was the RE/MAX real estate balloon, and that it was about to float off. Suffice to say, I enjoyed the show in a whole new way.

In the early 2000s, when I was in college, diabetes and related health issues began to catch up with James. He had to shutter Zuma, and eventually needed to have his left leg amputated below the knee. He retained his dark sense of humor, convincing a beleaguered nurse to let him leave the hospital with the severed limb in a cooler, citing religious reasons. James kept it in his garage freezer for a few weeks before bringing it to grandpa’s old farm with some old pals one weekend; they held a sardonic funeral for the leg and buried it there.

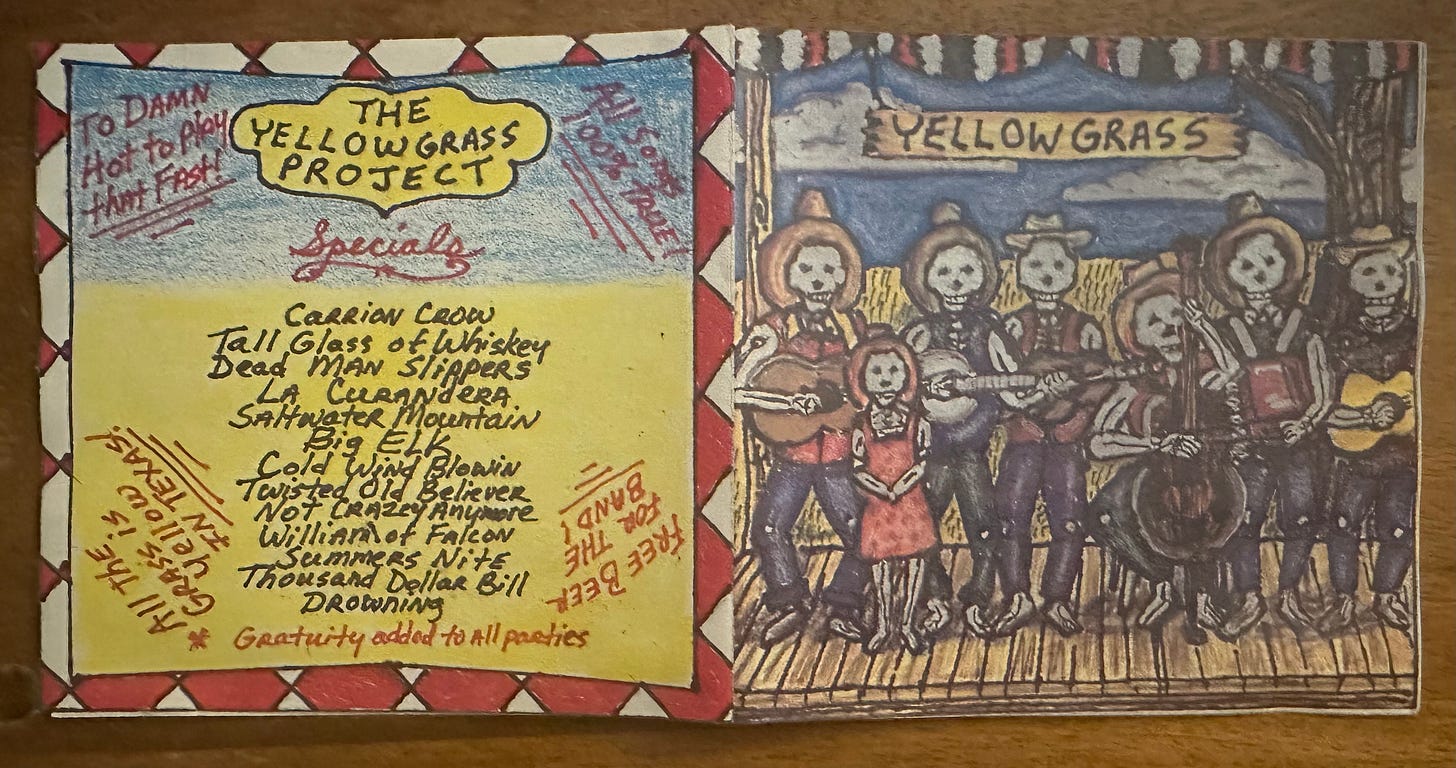

His friends thought of another way to boost his spirits: teaming up to start a band, which they called Yellowgrass. But soon, James was too sick even for backyard practices, and things were so dire he had to go on thrice-weekly dialysis while attempting to find a kidney-pancreas transplant.

Then, in 2008, he matched with an organ donor. After an arduous recovery, he was back in action—and Yellowgrass became his second act.

Meanwhile, I had started my career at Forbes, and by the early 2010s, I was carving out a role as the magazine’s music guy. It absolutely tickled James to read my work (he was especially excited when I got to interview Neil Young). And I began to report cover stories.

Toby Keith. Katy Perry. Kendrick Lamar.

But I never felt starstruck. I’d already had my Almost Famous moment in Austin, at age 13, when James took me to George DeVore’s afterparty.

South By Southwest, meanwhile, had become as important as the Grammys for music writers to attend. And I didn’t need to be asked twice to take another trip to Austin. That meant more shows with my uncle and aunt—and now with their kids, who were becoming music aficionados in their own right. I even got to watch Yellowgrass play South By.

James loved hearing about what I was up to in town, whether interviewing a not-yet-famous Ed Sheeran in a windowless green room or watching Skrillex pound gin-and-Red-Bulls on the terrace of the Driskill Hotel while I peppered him with questions for a story on the business of EDM.

At some point, the big music publications began to take interest in my work, and Billboard and Rolling Stone tried to lure me away from Forbes. Each time, it was a hard call, but I stayed—for good reasons—though I always dreaded telling James that I had turned down such cool gigs. But each time, he just seemed happy for me, proud of me, wherever I ended up.

I did my best to follow my uncle’s example of opening musical doors. I snuck my cousins into top shows at SXSW with platinum badges passes borrowed from Forbes colleagues. I took my cousins to my favorite venues in New York when they came to visit. My wife and I even brought Bridget to a Bob Dylan concert at the Beacon Theatre (unfortunately, it was one of the worst shows any of us had ever seen—he seemed thoroughly uninterested in being there).

Eventually, though, I realized my cousins already knew more about music than I did, even as a professional music writer. And why wouldn’t they, with James as their dad? Now in their 20s, they had their fingers on the pulse of what a new generation was listening to—music that I, even in my early 30s, didn’t know. My cousins became my A&R skunkworks, helping me identify the next wave of stars for projects like the Forbes 30 Under 30 Music list.

Charli XCX. Lizzo. Lorde.

At the same time, Yellowgrass continued to grow its cult following, thanks to its heady mix of bluegrass, folk, and rock. With James as its frontman, the band became a local staple in Austin, playing venues from the White Horse to the Elephant Room—and even co-headlining the Saxon Pub with my old pal George DeVore.

Yellowgrass kept making music, releasing several independent albums. During the early days of the pandemic, James sent me an email. “Hey Zack,” he wrote. “Thought you might enjoy the latest from Yellowgrass. Love ya.” He attached a song the band had just recorded, a deadpan dirge that sounded like Johnny Cash playing a New Orleans funeral. Its title: “We’re All Gonna Die.”

That was James. And his gallows humor persisted even as his health declined. Kidney-pancreas transplants rarely function for more than a decade; by the time the time Covid-19 reared its head, James was back on dialysis three times a week. As usual, he never complained, even when he could no longer play Yellowgrass shows.

James found other ways to express his creativity, auditioning—and earning a callback for—the reality show Master Chef. He started collecting Native American art, vintage toys, and all things Western; a ceremonial buzzard bowl landed him on Pawn Stars briefly in 2021.

When I became a dad the following year, James was among the first to welcome my daughter, Riley. He and my aunt sent her a miniature piano, which quickly became her favorite toy. And now, despite being a month shy of three years old, Riley herself has developed eclectic musical tastes. In addition to asking for “Baby Shark” and “Wheels on the Bus,” she often requests grownup artists from Nas to Taylor Swift to Tito Puente.

When I arrived in Texas for my last visit with James, I attempted to prepare myself by playing some of the great music we’d listened to together. As I sped along the highway, I queued up a few familiar albums.

No Code. Californication. And Out Come The Wolves.

But the more I listened, the more I just felt like myself. And it reminded me of a wonderful gift James gave me: He never tried to create my musical tastes in his image. If he had, I’d have been more playing Neil Young or Son Volt (which would have been great, too). James just opened the door to the metaphorical record store and guided me to a few areas I might like—the best kind of music discovery.

As I got closer to his house, I started playing songs by Austin bands. And I was instantly transported back to the summer of 1998.

“Dear Kate” by Dynamite Hack. “Boom Boom Baby” by the Ugly Americans. “Bend But Don’t Break” by (who else) George DeVore.

My rental car was suddenly grandma’s Cadillac, and James was right there next to me.

And James was there when I arrived, along with my aunt and my cousins, still himself. Though he was well on his way to leaving far too soon, he was going out on his own terms. On my last day in town, he seemed to be in such good shape out there on the patio that, before I left, I told him how much I was looking forward to giving him a video call with Riley when I got back to New York.

I went inside to gather my things, and by the time I went to say goodbye, he’d already retired to his bed. I told James I wouldn’t be who I am if it hadn’t been for him. And I told him how much I loved him. His response: “You’re fucking awesome, I love you man.”

We had talked about how he believed in reincarnation, and how he wanted to come back as a red-tailed hawk. So I told him about my little outdoor space with two small coral-bark Japanese maple trees, and that I’d love for him to pay me a visit if he ever made it up to New York.

“I’ll be looking for ya, on your patio,” he said. “I got it.”

Those words, which Bridget captured on video, turned out to be the last ones James ever said to me. The next morning, Mary Beth called me to say he was gone. We all knew it was coming, though of course it didn’t make the moment easy.

When I got off the phone, I wandered toward the window and stared out. Suddenly, something caught my attention. I could barely believe my eyes, but there it was: a red-tailed hawk, zooming above my street, headed west.

Thanks for reading. This piece has been a labor of love that occupied much of my mind this past month. If you enjoyed it, you might also like reading my remembrances of my dad, my cat, and DMX. And/or my articles and books.

Oh my gosh, Zack, one of the greatest things I’ve read, ever. I’m so sorry about the loss of your uncle, in human form. Love his influence on you… and now me believing in reincarnation. Thanks for sharing this!