Why Mood Is The New Musical Genre

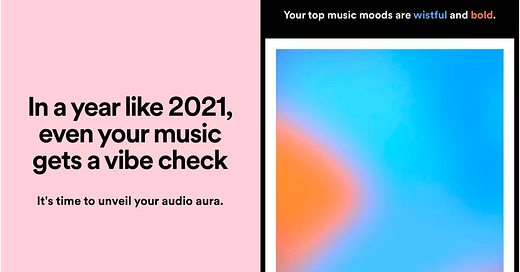

Traditional classification systems struggle to be relevant in an age where the term “chill” means more than “R&B.”

Greetings from paternity leave! Please enjoy this guest post by Tiffany Ng. In addition to doing some fantastic editorial research for me on We Are All Musicians Now and other projects this year, she served as culture editor at the Yale Daily News before her recent graduation. She’s also written for Vogue Hong Kong and High Snobiety—and understands far …

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to ZOGBLOG by Zack O'Malley Greenburg to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.